Brazil is home to around one third of the world’s largest rainforest, the Amazon rainforest, and is thus a prime candidate for talks about the conservation of forests and tree covers. The Amazon is particularly important to this discourse due to the sheer magnitude of the biodiversity that is housed by the forest, with over 390 billion trees, and with 16,000 plant species and millions of animal species.

Apart from being a humanitarian and ecological disaster within Brazil (and South America as a whole), the decline of the forest threatens to rid the planet of one of the biggest carbon sinks, thereby increasing carbon emissions that cling to the atmosphere. A tipping point is also a major setback for the scientific community, with 44% of the plant species inhabiting the forest having valuable medicinal properties.

The Persistent Threats

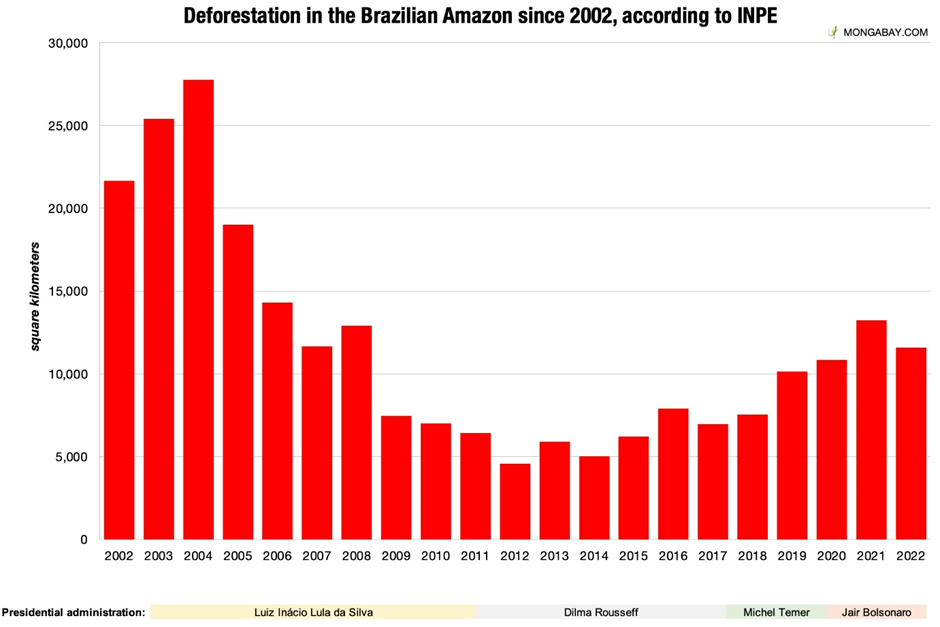

After seeing a historic low in 2012, deforestation of the Amazon in Brazil grew back to 2007 levels from 2015 to 2021. With the re-establishment of Lula da Silva’s administration, the Brazilian government has aimed to end deforestation and become a green superpower. This sentiment is further highlighted by Brazil being a signatory nation for COP15 and COP27.

Brazil provides a vital and contemporary case study for the various threats posed to forests around the world. The Majority of the forest cover loss can primarily be attributed to two overarching factors;

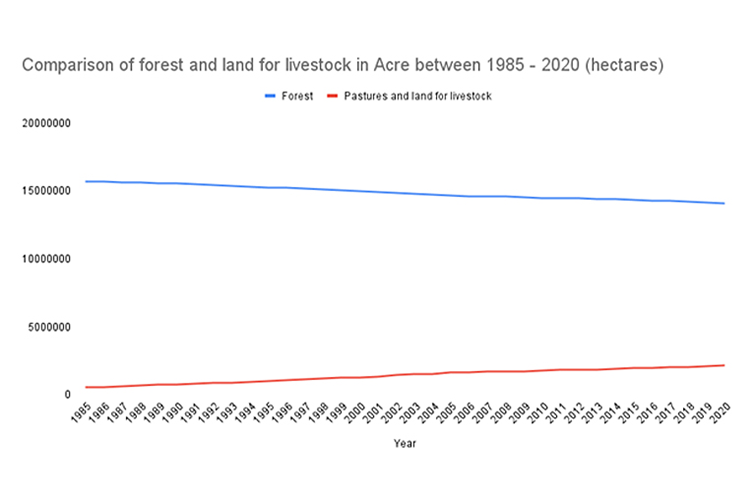

- Agriculture and Animal Husbandry – An ever-expanding cattle industry has become a major threat to many forested regions in Brazil. Cattle presence in Acre, one of the least deforested Amazonian states, increased from around 400,000 in 1990 to a record high of 3.8 million, with an 8.3% increase in the livestock population in the span of 2019-2020 alone. Cattle ranching has become a driver of deforestation, accounting for around 75% of the area that has been deforested.

- Legislation – The newly enacted Native Vegetation Protection Law (NVPL) has overridden the protection of several environmentally fragile areas. It has enabled concession of fines brought about by the violation of previous legislation while allowing for agriculture in areas protected by law. Additionally, the recently passed ‘Safer Food Bill’ gives full regulatory and administrative authority in approving and clearing agrochemicals for use to the Ministry of Agriculture, cutting out the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (IBAMA) from the decision-making process entirely.

International Opportunities

Due to the prevalence of forest cover loss in Brazil being a multifaceted issue, International and non-governmental institutions provide the ideal solutions in a globalised world in sorting out climate issues through collaborative development of policies. Meanwhile, due to the inherent link between the industries causing deforestation and the nation’s economy, curbing the trend becomes a sensitive affair.

- Securing Funding- Minor economic setbacks can be counteracted by international subsidies and funding like the pre-existing Amazon Fund under the UN REDD+ initiative. The country can also utilize the framework developed by the United Nations Strategic Plan for Forests (UNSPF) to mobilise Global Forest Financing Facilitation Network (GFFFN) in providing funding which has been maintained by the United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF). The funds are also crucial in maintaining monitoring capabilities in order to prevent illegal activities that also jeopardize conservation efforts.

- Reinforcing Carbon Neutral Development- Reinforcement of carbon neutral development will have the longer-term return of developing practices and legislature that will support conservation efforts. The Emission Reduction Payment Agreements (ERPA) system by world bank provides a solid foundation for the trade of carbon credits with government and private sector entities, providing thus a financial incentive in reducing emissions.

- Reviewing Legislature- Pre-existing legislative loopholes form a major part of illegal logging. Reports suggest that more than 90% of deforestation in the regions of Amazon and Cerrado in Brazil could be illegal in nature. Data on this issue is lacking due to legislature; the primary permit that allows for landowners to deforest (known as ASV) not having well defined information, making it difficult to distinguish between legal and illegal activity. Cooperation with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) can strengthen standards and practices for sustainable management of the Amazons.

Conclusion

Drawing upon Brazil’s example, we understand the shortcomings of forest conservation efforts, that primarily being economic demands and legislative constraints. When combined with insufficient funding via capital and manpower, these issues compound towards devastating consequences nationally and internationally. However, global sustainability organisations provide ample opportunities to circumvent these issues. International bodies can mobilise funds and minds in order to wholly combat forest degradation, thereby highlighting the need to maintain such institutions.